Data Mining

These outlets offer broader access and heightened speed making our daily routines more efficient. But what is the affect on the digital content we absorb? On the translation of information and imagery? Specifically, how do social media and Goggle impact images’ palpability? One can watch global history unfold, but the details we access online are inherently diminutive. Suffering generational loss through the “Xerox effect” – loss in quality when data is copied, transcoded, compressed or converted – and these platforms force imagery into preset scales confining the accompanying literature and language.

Data Mining examines categorical delineations between photography and painting in the digital era. By printing imagery onto canvas or adding a stroke of paint, does it shift a print to a painting? Cahan began his exploration of practice, material and category by questioning how painters like Picasso, Mondrian or Motherwells’ orientation may have shifted if they were working today. How would they define painting in the digital age?

In his new series, Cahan focuses on “data mining” used for marketing and promotion online; specifically the impact of the “web usage mining” process of capturing web users’ identity and browsing behavior on the circulation of fine art content. Applying this to the consumption of visual art, (commercially or culturally), has generated a proliferation of imagery and hasty details regarding artists that users have searched, bombarding us with content related to our previous online activity. For Cahan, this has affected our relationship to imagery by diminishing the tangible rituals associated with the production, assimilation and consumption of art. With this inundation of imagery, the visuals’ impact lessens. The screens between viewer and content reinforce removed engagement: people take photos of photos or artwork selfies they post on social media marking their engagement. Increasingly, the relevance of an artist or piece is determined by its likes or trending status. This leads some artists to shift their practice, research, and references from substantial to digital sources making work from and for the screen. Cahan’s new series negotiates these technologies and their impact on the references, production and oscillation of work as the art historical lineage progresses.

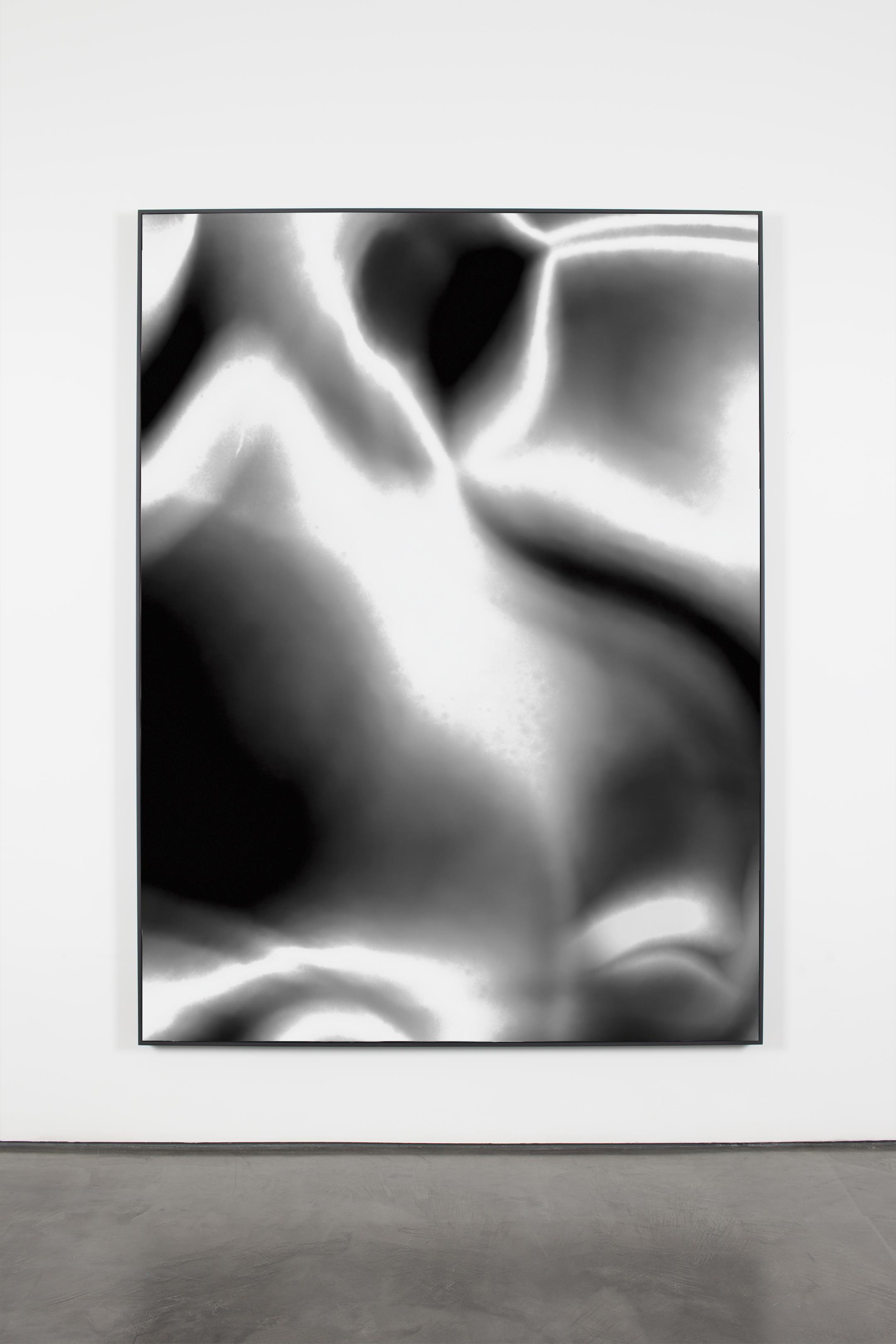

Cahan takes solarized photographs of water, develops and scans them into Photoshop, then prints them on fiber paper in a traditional wet chemical process derived from the origins of photography. Oscillating between analogue and digital, he then deconstructs the image with bleach, afterwards scanning this altered image back into Photoshop, where he digital paints over it and finally prints this several-times distorted photograph through a flatbed printer onto gesso-primed linen canvas, ultimately stretching the photograph and setting it within a graphite frame. Through this practice, he aims to recapture the rituals of analogue techniques and envelope the painterly into his photographic process. Considering the expansion of the painting genre and blending of formal techniques across categories from a historical perspective, Helen Frankenthaler’s 1952 technique of “stained color” can be seen as a precursor to Cahan’s cross-pollination of techniques and category bending. Cahan views his photographic process as blending formal aspects of painting – gesso, canvas, pigment – with a meshing of analogue and digital photographic techniques. Both artists cultivated their practice in response to shifts in the way their work oscillates and is consumed.

Cahan’s concept is oriented around the entropy of data and evolution of visual vernacular and art historical cannon in our digital era. The specificity of subject is irrelevant for him and is but a point of departure for considering representation and abstraction. Contemplating iconic imagery and Cahan’s exploration of the current status of visuals, the Greek “eikon” – that denotes “mirror-like representation,” “resemblance” or “projection” – is a classical parallel to Cahan’s probing of how artworks are captured, projected and as they shift across digital platforms become distorted and their meaning or substance diminished.

Abstraction has progressed from a manner of interpreting subject into our processes for integrating and absorbing visuals. As our global economy becomes more digitized, our ability to engage across cultures, space and time propagates, but historical and contemporary art content depreciates. Cahan’s new series examines how viewers’ level of engagement on these platforms has become more cursory and less perceptible given the over-saturation of images on social media and online. With the increased digitization of studio practices and platforms for presentation, Cahan focuses on the affect of technology on the lifespan and meaning of imagery. Cahan theorizes that, as globally connected citizens, our biggest relationship is to the screen. It is what we engage with most, and affects imagery we absorb through color-correction, aspect ratios, composition, the attention we devote to visual art and its significance and tangibility.

Cognizant of the shift in platforms for art consumption and the tools for creating works; investigating practice, material, and category is paramount for Cahan. With this series, he is less concerned with subject and more interested in the romanticism associated with practice as he circles his digital photographic process back to its origins of silver gelatin development. The nine photographs presented in Data Mining are titled “D.M.1” “D.M.2” “D.M.3” etc., in reference to the web usage mining practice, direct messaging as it correlates to online engagement with art. The numeric component orients the works to the photographic tendency of serialized editions. Data Mining considers the historical and categorical advancement of artists’ practices and the shifting language of visual vernacular as we progress further into the era of digital and global connectivity.